One of the most notorious titles from the original run of Action makes its return to print within the pages of Battle Action #5, out in now in the UK, hitting US shelves January 22nd!

COMIC BOOK YETI: Dan and Tom, thank you both for dropping into the Yeti Cave today. How is everything going up in the UK amidst the holiday season?

DAN ABNETT: Happy to be here. Thanks for having us.

TOM FOSTER: Hi there! Nice of you to have us. I gave myself a Christmas present of not really checking the news for a couple of weeks, so all I can tell you is that there’s an icy bit on Pollockshaws Road that you want to watch out for. Take the legs clean out from under you.

CBY: Thanks for the tip (stay alert out there, folks)! While I know you’ve both worked for Rebellion previously, can you share with our readers a bit about how you two met? What led to being paired for this revival of “Death Game 1999” – a notoriously violent title in the original Action catalogue? Do either of you have insight as to why they saved it until Vol. 5 of Battle Action for you two to pick up?

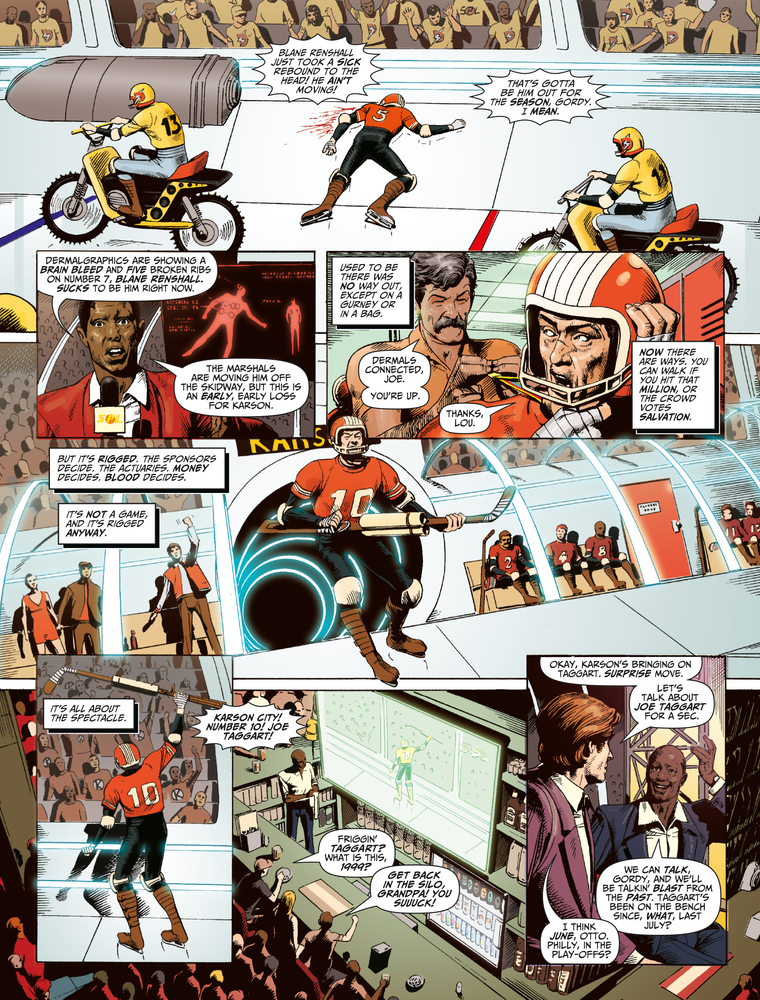

DA: It was the editor’s call to pair us up, which suited me fine as I think Tom’s work is fantastic. Garth invited me to write a story for this second series (he got me to do “D-Day Dawson” for the last one), and he was keen to feature more of Action’s ‘non war’ strips. So the choice was mine. “Death Game” is, as you say, a notorious strip, and after considering a few different ways to re-invent it, I decided it would be best to do it straight, as it always was, whilst acknowledging that it was the template for all the classic ‘future game’ stories in 2000 AD. I liked the idea that the game was still grinding on, season after season, almost normalising the violence for the audience. I think that’s why I decided to treat it as a slice of a totally ‘normal’ sports broadcast, with commentary, fan reaction, and studio pundits.

TF: I couldn’t say why they saved it so long, but I think they brought it in because there was a sense that the Battle side of things was dominating a bit. I’ve never been all that into war comics, so I was glad to get offered something a bit less gung-ho. Plus researching all those weapons and vehicles and uniforms can eat quite bit into your drawing time. Regarding why they chose me, I think they probably felt that someone with quite a traditional style would help keep a sense of tonal continuity with the strip – rather than having a huge shift in the way the world was presented. As for how Dan and I came to meet, I think this is the first time I’ve actually met him – and I must say he’s looking radiant.

CBY: I was born about 20 years too late on the wrong side of the Atlantic to catch Action in its original form. I went back to look for some of the old issues, and Tom, you definitely captured the visual vibe of the inking in the originals and gave it its proper due. What discussions did you have around how to approach the art? You could have taken the story and imagery in so many directions, but you really captured a sense of picking up in the same space (if not time) the original left off. What led you to the relatively faithful interpretation as opposed to a more idiosyncratic reboot?

DA: I certainly wanted it to ‘feel’ like the classic strip, with a few nods to the way modern sports are broadcast and presented. I wanted to leave Tom as much elbow room as possible. I felt it had to seem both authentically real, and also showbiz glossy with the razzmatazz.

TF: Dan provided a pretty clear idea of what he wanted in the script, but with enough room for interpretation to make my job as enjoyable as possible. The actual sports equipment was to remain largely unchanged in its appearance (as is generally the case in sport), with only the TV studio and elements of the arena betraying the advancing years. This was exactly how I would have wanted to approach things if left to my own devices, so it worked out very well. If anything, I tried to tone down some of the stylistic flourishes in the original strips and keep everything looking as functional and traditional as possible to keep the thing grounded. Colour was an important consideration too, since that wasn’t really a feature of the old strips and had to be interpreted more or less from scratch. Since ‘Spinball’ is largely a spectator’s sport, the whole thing was geared towards being as candy-like and toyetic as possible, with an emphasis on primary colours, simple shapes and dangerously imitable behaviour.

CBY: Dan, I think you found a balance that helps a reader feel like they’re picking up the same thread and dusting it off years later. Tom, we mentioned the faithful reinterpretation of the original run, and I’ve seen your grid/perspective line work-in-process imagery you’ve shared online. Can you share with our readers a bit about your illustration process; both your preferred techniques and materials? Dan, what sort of cues do you write into your scripting process to set the scene – how much directing the page takes place? You’re both veterans of the medium; what most effectively allows you to communicate your creative intent to each other?

DA: I really just tried to keep a sharp eye on the cutting between shots and scenes, the switches between one point of view and another, and to layer the cuts between one narrative line and another so they all added together to form one. I might have asked for a close-up here or a wide shot there, but mainly I wanted to make sure Tom had enough room on each page for the more violent or explosive moments.

TF: I generally stick to practical materials as much as possible. I do my colours and perspective grids digitally as the latter saves a lot of time and doesn’t actually show up in the finished art anyway, while the digital colouring allows me the greatest opportunity for editing. All the penciling and inking is done practically, with a clutch pencil, a sable brush and technical pens. I find these give me greater control over my line work than a graphics tablet, plus I have the option to sell my original pages. I used to use a lot of 3D digital models, but I found they were slowing my development as a penciler and were a bit joyless to work with, so I very rarely use them now. I don’t think I used any on this strip. In terms of communication with Dan – luckily his script was clear enough to not really require any back-and-forth. It was very straightforward to visualise his writing. The only thing I ever considered asking about was a bit where Karson City had just made a ‘250 yard push’ before being intercepted at the ‘thirty yard trap’. This meant, by my calculations, that the rink was a minimum of 840 feet long which seemed so unimaginably big as to totally dwarf the players in wide-shots. But I figured that’s something you can play pretty fast-and-loose with visually and nobody will really notice.

CBY: Dan, you mentioned Norman Jewison’s 1975 film, Rollerball (starring James Caan) in your intro to Death Game 1999, but another 1975 film, Paul Bartel’s Death Race 2000 (starring David Carradine & Sylvester Stallone) clearly provided some influence on the title, at least. 1987’s The Running Man (unrelated to the Action comic, based upon the 1982 Stephen King novel) and 1994’s Mutant League TV show are immediately evoked as similar bloodsport-related media released following the initial run of “Death Game 1999,” and Jerrold Freeman’s 1972 Kansas City Bomber also came to mind. I may be making specious connections, but beyond the source material, what other influences inspired both your narrative and aesthetic for this resumption of this story after so many years?

DA: Rollerball was always the starting point, as the strip, like so many in the early Action, was ‘directly inspired’ by contemporary pop culture. Most of the films you mention were in the back of my mind too, but I was also thinking about how the original strip had run with the concept and depicted it, and how that had later influenced series like “Harlem’s Heroes” and “Mean Arena.” Like the war story, the ‘sports story’ (usually soccer) was a very popular staple of British comics in the sixties and seventies, and I thought it was fascinating to see how the conventions of that had been co-opted for science fiction and brutal action.

TF: I watched those first three films you mentioned around the time I started on the strip. Rollerball was the most obvious influence and I looked at quite a bit of the concept art for it when deciding on the design elements and colours. The Running Man was an influence on the design of the arena (blue strip-lights, I’m looking at you) and the atmosphere during the moments of heightened emotion. They use a lot of red gels and dry ice in that film to compensate for the fact that they don’t really have a big sports arena set, like Rollerball had. It’s effective at times, but you can’t help but feel it would be nice every so often to be able to cut to a nice, big wide shot with lots of lighting and extras.

So I tried to have the best of both worlds, since I didn’t have to worry about budget. I’d have nice big sweeping wide shots with clear, white lighting whenever the mechanics of the game were the focus, but as soon as the brutality or emotional intensity ramped up, I’d start to redden the lighting. I figured I’d leave it up to the reader whether this was some kind of dynamic lighting the arena used to heighten the drama or just a little creative license on my part.

CBY: Now that it’s rolling again, how many installments should our readers expect from the two of you for “Death Game 1999?” Since Battle Action wound up the series in 1979 (by then named “The Spinball Wars”), how much space are you being given to expand, and perhaps conclude with some greater level of finality, the story of long-running series star, Joe Taggart?

DA: It’s just this one shot for now, but I’d love to continue with it. I think there’s a lot we could do, if Tom is game (pardon the pun).

TF: I genuinely have no idea. I really enjoyed working on it, but I don’t know if there’s a plan to do more. Schedule allowing, I could see myself diving back in though.

CBY: The story is certainly left open-ended enough to carry things onward. So, Spinball is played between two teams of convicted felons, wearing ice skates with some team members on motorbikes. There’s a black pin in the middle that seems to be crucially important, and points are scored in the tens of thousands. Do both of you feel like you have a cohesive idea of the rules of Spinball? I know from a few of my projects that writing sports action requires different details and pacing than dialogue-heavy scenes. What sort of play-by-play planning went into delivering the vivid interplay in the arena you’ve been able to achieve on the page?

DA: Yes, I understand the rules in so far as I reckon I can fake authenticity. But in a very real sense, no… I’m not sure the original writers of the series could have explained the rules comprehensively. I read back over the original series and tried to emulate the form, the ‘highlights’ and the sense of play-by-play.

TF: That’s a good point. Apparently, the makers of Rollerball had no idea of the rules of the game until the arena set was already built because they had to first figure out what was possible in terms of action. We didn’t have quite that problem, but when you don’t have a clear bible to work from, or even a nailed-down sense of how the rink is laid out, that’s something that you have to really spend some time figuring out before putting pencil to paper.

In stories like these, the mechanics of the game tend to be quite amorphous and geared toward the dramatic beats of the story, but visually, there has to be some functional sense to it all. There’s a suggestion in the way the original strips were drawn that the rink was circular (like Rollerball‘s), with one black pin – possibly in the middle. But this story was written as a largely end-to-end game, with a thirty-yard line and obstacles that specifically block the ‘straight down the middle’ path to the black pin – all of which suggests linear advancement. However, the ball still needs to get launched and spin around the track like a roulette wheel.

So, in my design of Spinball, there are really two black pins at opposing ends. There are two primary sets of flippers that block the most obvious path to the black pins and force play out towards the perimeter, with several lower-scoring pins arranged in a sort of zig-zag pattern along this outer path. The sides of the rink are all curved, with no hard corners, so the ball (and play) can loop around and thereby reverse the fortunes of the game. Since they’re skating, the players will often find it a lot easier to maintain momentum by following this circular direction of play than to make a hard volte-face, but there are rewards for those skilled enough to take a more direct course. You can see the basic layout behind the studio pundits on page one.

CBY: I don’t want to spoil anything, but at one point, a character mentions wanting to switch the channel from Spinball over to Aeroball, and Inferno League and European Street Football both garner a mention. (I remember when I first learned about the absurd rules of Australian Football, I felt inspired to make up an entirely new sport called Beatball.) Did you think through what these other sports would entail at all, both structurally and visually, when you came up with the names?

DA: Yes, but in the main, these are Easter egg references to 2000 AD‘s other ‘future sport’ strips. I like the idea that Spinball is the original – and nastiest – of them all. Certainly, when “Death Game” returned to the comic (having been one of the strips that almost got it cancelled the first time), Action was a more sanitised comic, and “Spinball Wars” was famously de-fanged compared to the violence of the original run.

TF: Thank god we never saw them.

CBY: I’m keen to explore other examples from the genre. Tom, you’ve been putting together lots of great work for Rebellion in 2000 AD and The Judge Dredd Megazine in recent years, and Dan, you’ve been writing comics nearly my entire life for major and indie publishers on both sides of the Atlantic. I mentioned, Tom, your ability to achieve the look of the original comic, and it leads me to wonder; how do you both approach adapting someone else’s characters or working with intellectual property not of your own creation? What changes in your design and drafting process depending on whether a story is wholly your own or not?

DA: Well, I think I do – and have done – an awful lot of that. It’s a matter of entering into the spirit of the original, treating it respectfully, trying to find what makes (or made) it so well liked, and then imagining myself as a reader or fan… what would I most like to read?

TF: Generally, I like to keep a character on-model. Whatever the reader sees in their head when they think of the character is what I aim for. If that’s not 100% established, I’ll try to establish it – try to pick through the various interpretations to figure out what parts are the character and what are just a stylistic choices by one particular artist. Then I’ll try to refine those core elements as much as possible: make sure the outfit makes physical sense; give the props the right weight and a nice balance of curves and straight lines; ensure the character’s face has nothing in it that doesn’t BELONG to that character – they shouldn’t look too specifically like any real person, unless by design.

This means I can then draw the character time and again, keep them consistent, and not be constantly asking myself what they ought to look like – and the reader doesn’t get pulled out of the story because the character doesn’t seem like the one they know.

CBY: There’s an obvious commentary on incarceration as indentured labor for enterprises prioritizing profit over justice – it’s at the core of the existing prison system in the United States (and elsewhere). There’s also a succinct and brutal examination of class and entitlement that I won’t spoil for readers. What can you both add regarding your perspectives when you were given the opportunity to relaunch this series in the current social climate and how you decided to take things in the direction you have with Death Game 1999?

DA: For a start, the whole “bread and circuses” thing is truer today than ever. I think Action, and 2000 AD (even more with 2000 AD), had very strong satirical threads running through them. I think we tend to forget that aspect of the original publications sometimes. They offered political and cultural comment, dressed up in outlandish sci-fi and raw violence. “Death Game” is a very ‘obvious commentary’ as you put it, perhaps simplistically so, if we think of it coming from a ‘simpler time’.

Ironically, in this allegedly more sophisticated era, I returned to “Death Game” and still wondered if I was making its point clearly enough. Sanctioned, explicit violence as a popular distraction from social woes… you depict that, and there’s the danger that the violence and the vital energy serves as a distraction anyway.

TF: Class is always a big issue as it exacerbates so many other social issues. The wider the gap between those at the top and everyone else, the bigger the consequences for those deemed second-class citizens for whatever reason. Since it concerns them directly, it’s generally the biggest and most immediate issue that the upper crust want to deflect from. So if they can exploit one group of the underclass to distract, pacify or otherwise neutralise the other, they’re onto a winner. Thus: Spinball.

CBY: I think that ties things up nicely. To close, we always invite our guests to share a bit about the work unrelated to their own projects that has inspired them lately. What comics, films, literature, music, art, etc., have been catching your attention lately? What should our readers check out after they give Battle Action Vol. 3, #5 a read?

DA: I’ve been (belatedly) reading my way through Ben Aaronovitch’s Rivers of London novels, which are fab, and also (belatedly) working through the TV shows Cardinal (Nordic noir crime but in Canada) and “Based on a True Story”. I’d also recommend Tim Winton’s new novel, Juice (a post-apocalypse change of pace for him) and Creation Lake by Rachel Kushner (genre defying and fascinating).

TF: I read a lot of Agatha Christie and am currently working my way through the Poirot books. I’m also painting my next project in acrylics, so am looking at a lot of Glenn Fabry. There’s something about his work, particularly in the 90s, that just seems impossibly solid. He has such a strong grasp of form and anatomy that he can reinvent them and still make them look totally real. His brief run of Ninja Turtles covers are particularly baffling to those of us who must make do with a human brain. Oh, and there’s a Youtuber called Stuart Millard who does exceptional and very funny dissections of old British telly. I would recommend checking him out.

CBY: Brilliant, I’m about twenty pages into Juice right now, so I’m glad I’ve got the rest to look forward to reading. Thank you both for stopping by the Yeti Cave, gentlemen! For our audience at home, please share any portfolio, publication, and social media links you’d like everyone to check out, and we wish you the most enjoyable time over the holidays!

DA: Thank you. You can catch up with what I’m up to in 2000 AD (with “Azimuth,” “The Out,” “Brink,” and “Feral and Foe”), The Judge Dredd Megazine (“Lawless”) and my Warhammer novels (the latest being The End and the Death, and Interceptor City). I’m also to be found on Facebook and Insta.

TF: Thank you! You can check out my Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/tomfosterart/ and my BlueSky at https://bsky.app/profile/tomfosterart.bsky.social