The race to populate the heavens with orbital satellites is reaching epic proportions. While a fairly young private industry—SpaceX only successfully launched its reusable medium-lift Falcon 9 rocket for the first time in 2010—it’s also burning with more thrust than a first-stage booster. Consider that Morgan Stanley predicts the space industry to eclipse $1 trillion by 2040 and you begin to recognize why so many parties are throwing their business models into the ring.

The HBO documentary Wild Wild Space highlights this race with great alacrity, illuminating the difficulties involved in the Herculean endeavor by following three players in the field: Rocket Lab, Astra Space and Planet Labs. Some reveal themselves as real contenders, others pretenders. Firmly position Rocket Lab, and its founder Peter Beck, as the former. Raised in the non-futurist pastoral beauty of south New Zealand, Beck managed to evolve building rocket bikes in his shed into a humble start-up that has grown into SpaceX’s most viable competitor—all without ever earning a college degree. Rocket Lab’s Electron is now the third-most-launched rocket in the world; its larger successor, Neutron, expects to raise its sibling’s payload by more than 4,000 percent, making it a legit contender to the apex Falcon 9.

Maxim sat down with the brilliant founder and engineer, who was recently knighted into the New Zealand Order of Merit, as Rocket Lab celebrated Electron’s 50th launch—and prepares for Neutron’s arrival sometime next year.

One of the big bullet points of your journey is that you never went to university, and now you’re running one of the world’s top rocket companies. How did you go from building rocket bikes in your garage to this?

The plan was always to go to university, it was just never that convenient. There were no university courses that covered anything even remotely to what I was interested in doing, so the fastest pathway to learn how to do what I wanted to do was to just build it. So I felt I needed those hand skills right up front to be able to build what I wanted to build. And I’ve always believed that truly the best engineers are the ones who can build what they design and think of. So that was the original plan: get a trade under my belt and then go to university and then ultimately go to work for NASA. And so I sort of started down that path and I was building rockets.

Festival of Speed in Dunedin (Rocket Lab)

I always ran two shifts in my life: the day shift where I have to do real work, and then the night shift. And whether I was at Fisher & Paykel or the government lab, I’d always be building rockets and whatnot. And really, I remember a time that when I was working for a government lab, I was called as an expert witness for some composite failures because I had a deep knowledge base and worked deeply with composites. And they said, “Oh, you can’t be an expert witness because you don’t have a degree.” And then the government lab said, “Well, Pete, you should really go and get a degree.” And the craziest situation occurred where I would have to take Design 101 classes in the morning, but yet in the afternoon I’m supervising a final-year Ph.D. at the government lab. So that was not a good use of my time.

Did you find the humor in that or it was just too absurd, like, “This is pointless, get me out of here?”

Yeah, no, I’ve never had any spare time in my life. And I think there’s two ways you can learn stuff: You can read books and do it, or you can go to university. You can go to university and you can learn about a shaft breaking, or you can go into industry and break a shaft. Now if you screw the calculus up at university, you get a D. If you screw the calcs up in industry, there’s a shaft on the floor and you get fired. So there’s a much higher impetus to make sure that you do those calcs right. But I think ultimately you learn the same thing.

When I was at the government lab the plan was always to go and work for NASA, and I was kind of working a resume together that I thought would be useful. And the resume consisted mainly of rocket engines, rocket bikes and rocket packs and all this sort of stuff that I’d produced, but of course, devoid of any kind of actual qualification.

And then I went to America on a rocket pilgrimage for about a month [in 2006, right before starting Rocket Lab] and visited all of the places that I’d dreamed to work and I learned two things. Most of these companies only do what the government pays them and tells them to do; they don’t take any risk and do anything that’s kind of interesting. And secondly, for a foreign national from New Zealand with no university degree at all in any field, the probability of gaining employment was zero.

So you’re faced with two options: Go to a university in New Zealand, then go to another university in America, and then maybe get some role a decade down the path. I don’t have a decade of time to wait. So on the airplane home for half the flight I was depressed, and the other half I was invigorated. By the time I’d landed, I’d doodled a logo for Rocket Lab, thought of what I was going to do, and then just put a sign up on my workshop door and started.

That flight seems like one of those crossroads that is a pivotal moment.

Yeah, but at the time it never felt like a big decision. It just felt, “Okay, this is the only logical solution, so we’ll just do this.”

So you return to New Zealand and meet [internet millionaire] Mark Rocket. How were you able to convince not just Mark but the New Zealand government—your first round of investors that—”I have no education. I built a rocket bike, trust me with this next endeavor.” You have said you’re not a salesman, how did you do it?

Well, I think I’m very logical and honest. And look, I’m not a salesman in the sense that I can talk bullshit, but I can certainly lay out a vision of what I think needs to be done and tell the story about how to get there. So I’d heard Mark on the radio because he had recently bought a ticket to fly on Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic, and I thought, ‘Well, here’s a man clearly passionate about space. In fact, passionate enough to change his name. I wonder if he’d be interested in investing in my little company?’ And he invested a small amount of money that got us going, and then ultimately I bought him back out. But I guess the real pivotal moment was going to Silicon Valley. That was a much bigger step.

And then from the government side, it’s quite funny really, because before I started the company, I thought, ‘Shit, this might be a little bit illegal. I’m not sure if anybody can just start building rockets in their garage.’ So I went and sat with some ministers down at Wellington at the government and said, “Look, this is what I want to do.” And they kind of looked into me and saw that I was working for a government lab. I’d made a pretty decent reputation for myself of not being a nut job, but ultimately what the minister will tell the story is that he only agreed to meet me because he wanted to see just how nutty this guy might even have been. But he actually ended up opening the company a few weeks later, so we managed to turn that around.

But yeah, like I say, really one of the biggest pivotal moments was going to Silicon Valley because I sort of putzed around in New Zealand, bootstrapping the business, getting little DARPA contracts and little Lockheed Martin contracts and whatnot. And I would sort of fly to the US, pitch some ideas, managed to get some funding from DOD or whoever, then come back to New Zealand and execute them. And we quickly built a reputation of doing amazing things with no money and always executing. So DARPA funded this small amount of money to develop this new rocket engine. We came back and we executed. And we did that time and time and time again.

That was the Atea rocket?

It was actually after Atea. So we launched that and that kind of got everybody’s attention, and I found myself in some interesting places: Lockheed Martin Skunk Works, DARPA, those kind of folks. And we’d kind of bootstrapped the company from 2009 to 2013 on these little contracts, bits and pieces. And then 2013, I jumped on a plane once again and went to the Valley. And at that time I knew absolutely nothing about venture capital.

This story is full of ironies, but the irony of that is that everybody in New Zealand said, “Ah, don’t go to America. They’re all sharks over there, and you’re going to get chewed up and spat out,” and all the rest of it. Now, the irony in that one is actually it’s New Zealand venture capital who were the sharks, which I’ve devoted the last 10 years of my life to fixing that, but that’s a whole other story in its own right.

So anyway, went to Silicon Valley and I gave myself three weeks to come home with a check or be run out of town. And for the first week, I just went and visited a whole bunch of startups to try and figure out how this whole venture capital malarkey works. Who are the good people in the industry, who are the not so good people in the industry, etc. And I needed an investor that had a great vision, but also could understand the industry that I was trying to play in. And in the end, I only actually pitched to three folks. And Vinod at Khosla Ventures was one who I pitched to who ultimately led the A round. And I look back on that, and it was a $5 million round. And at that time, that was an insane amount of money. It’s not like it was in 2021 where a college kid with a printed rocket could go and raise $100 million bucks.

It was really a stretch. Like SpaceX was embryonic, certainly unproven. And the biggest challenge I had was at that time, Richard Branson had decided he’s getting into small launch. So everywhere I went, it’s like, “How are you going to beat Richard Branson? He has infinite capital, and you are just this little guy down in New Zealand.” Which once again, a story of irony. We ended up buying that whole facility for 16 cents on the dollar from Richard Branson when he went bankrupt, which was a very happy day. But anyway, we raised that first round with Vinod and then spent the next few years on the treadmill in Silicon Valley raising rounds. We raised the B Round with David Cowan from Bessemer, and I think within Bessemer I still hold the record for the most unusual pitch because I turned up there with a rocket engine literally under my arm and stuck it on the boardroom table.

And then I tried to figure a way to show them the scale of the market opportunity. So I used my entire luggage allowance to fill up suitcases with bouncy balls. And at the end of the pitch, I had the sack of bouncy balls that I hoisted over my shoulder and poured out on a boardroom table. And there was two dozen people around the boardroom table, and these bouncy balls just went everywhere, and they bounced in people’s coffee and they bounced behind cabinets and absolutely everywhere. And I did that to just explain each one of these bouncy balls represents one satellite that needs launched in the next five years — they’re picking bouncy balls out of that boardroom still to this day, but it demonstrated the magnitude of the opportunity.

At that time there was still no way to get these satellites up there. So were people planning, building and concepting these satellites without a device to get them up there?

Yeah, and SpaceX was still starting with their Falcon 9. It wasn’t at the launch cadence it is, but the market that we were really initially focused on was small satellites. We weren’t really addressing necessarily the mega constellation market. So there was a huge boom of small satellites around that period — the Planet Labs of the world which is featured in the [Wild Wild Space] documentary and many, many others.

After you raise money, was the development and the launch of Electron what elevated Rocket Lab into the next league?

Oh, absolutely. As it stands today we are the third most frequently launched rocket in the world. It goes SpaceX, China, Rocket Lab, Russia, Europe, India, so on and so forth. So definitely on that front. And of course, at that time we were tracking up to 140 companies trying to build a small launch vehicle like Electron. And we were not the pre-ordained winners here. Like Richard Branson spent exactly $1.2 billion getting his rocket to first flight, which is $1.1 billion more than we spent. So it wasn’t like a sure thing that these little guys down New Zealand were going to kick Branson’s ass. But that’s kind of how it turned out.

With all the competitors who have died on the vine, what do you see as your unique selling point? What is your secret?

Look, as you saw from the documentary the industry is full of… The great thing about the space industry is that you can say these wild-ass things and people will believe you because it’s hard to disprove and everyone gets super excited. But that’s also the downfall of the space industry. And at the end of the day, it all falls back on absolutely meticulous engineering and execution. We have a saying here at Rocket Lab: ‘If you take a shortcut, the Rocket Gods come around with a baseball bat.’ And Astra was a great example of an experiment into how crappy you can build a rocket before it works. Where is the margin between crappiness and working good enough? And as they found out the hard way, there is no margin. It has to be Ferraris, it has to be perfect. And that ultimately was their downfall.

Now there’s a number of other companies, like I said we were tracking 140 at one stage, and their downfalls were sort of various. But at the end of the day the Rocket Gods do not accept any mediocrity in engineering. And I would say building a rocket company is running through a maze at night, but instead of a dead end just being a dead end, the dead end has a cliff. And if you run too fast, you just fall off the cliff and die. And one of the reasons is that if you make a technology decision and you go down that path, by the time you realize that path is wrong, you spend all your money. So you cannot make the wrong technology decision, you cannot make the wrong business decision, you cannot make the wrong infrastructure decision.

There’s just no room for any bad decisions. And I think there’s a good reason why the two most successful space companies or rocket companies in the world right now are led by engineers. It’s because as a leader of the company, you’re constantly trading business decisions off with engineering decisions, and they’re mutually exclusive.

I love the euphemism. Do they all have to be Ferraris, or can some be Toyotas or Hondas? Meaning affordable, but also incredibly well engineered. Like one could call the Neuron and Falcon 9 a Koenigsegg, the Electron a Ferrari. But is there a room for a smaller, cheaper, but incredibly well-engineered and built rocket, or do they at minimum have to be Ferraris?

Yeah, I think it is probably a misnomer to actually apply those kind of labels to it. The Ferrari is a minimum viable product. Astra thought that a Honda was a minimum viable product; it’s just not. There is no warranty called ‘Halfway up.’ It’s either perfect or it’s international news, one of those two. Those are the digital outcomes that you face every time you launch: Am I going to be on the front of New York Times or is this just going to be a perfect launch? That’s it. There’s nothing else.

Electron just celebrated its 50th launch. I know you make parts for other builders, and satellites as well, but is Electron your bread and butter, where you make your revenue?

52 in fact now, every couple of weeks we’re launching. But no: two thirds of our business is spacecraft and satellites. One third is launch. And that will change when Neutron comes online because, look, it’s an unashameable Falcon 9 SpaceX competitor. Same payload, capacity thereabouts. The way we describe ourselves is an end-to-end space company, which there are no other. Literally a customer can come to us and they want to put a communication satellite over Brazil, for example. We have the ability to design the satellite, build the satellite, launch the satellite, and operate the satellite all from under the one logo because we can build, design, launch and operate satellites, which is an entirely different business model to the space industry. A few years ago it was all government [operated]. Well, the next iteration on that business model is: it makes no sense to just be a rocket company, just be a satellite company. What makes the most powerful sense from a commercial standpoint is if you can do everything under one roof.

Don’t SpaceX and other competitors build satellites, or they just worry about the launch?

Well SpaceX is a bit of an unusual beast because they build their own Starlink satellites and they launch their Starlink satellites. And I think that’s a good analog for the power of this model. Unless you can build and launch your own satellites, nobody is going to be a competitor to Starlink because Elon can just put another one up next week. So that’s where it’s all going. And I’d say that we are really the only competitor to SpaceX in that sense. But the difference being is we don’t just build our own satellites, like Elon, we build satellites for everybody else as well. So it’s really an example of one.

Electron has a roughly 700 pound payload limit, and the Neutron has a 29,000 pound payload limit. So we’re really talking about completely different quantum categories. What are the type of satellites you launch with a Neutron or a Falcon 9 versus an Electron?

100%. So between those two rockets, we can lift about 90% of all of the satellites in the world. Generally [Neutron would do] mega constellations. So you’re launching large numbers of small satellites that typically weigh sort of 100, 200 kgs each, sometimes slightly more. Electron is great at putting up one or two of those, but when you need to deploy a whole constellation of thousands of them, then you need the larger vehicle like Neutron to deploy those constellations into lower orbit, just like Elon is doing with Starlink.

The first launch of the Neutron is slated for 2025. Are you still on schedule?

Well, look. So saying are you on schedule and a rocket program in the same sentence is generally hard to consume. Right now we’re on track for sort of mid-next year to put one on the pad, but we always caveat that with, it’s a rocket program, so if you have a bad day, it’s a bad day. So those can easily change. But currently that is scheduled to get the vehicle on the pad, and if it’s not, then it’ll be near abouts then.

I know these are not ‘pie in the sky,’ they are realistic goals, but can you tell me a little bit about the two spaceships that are going to go to Mars? And you’re also working on a Venus project, correct?

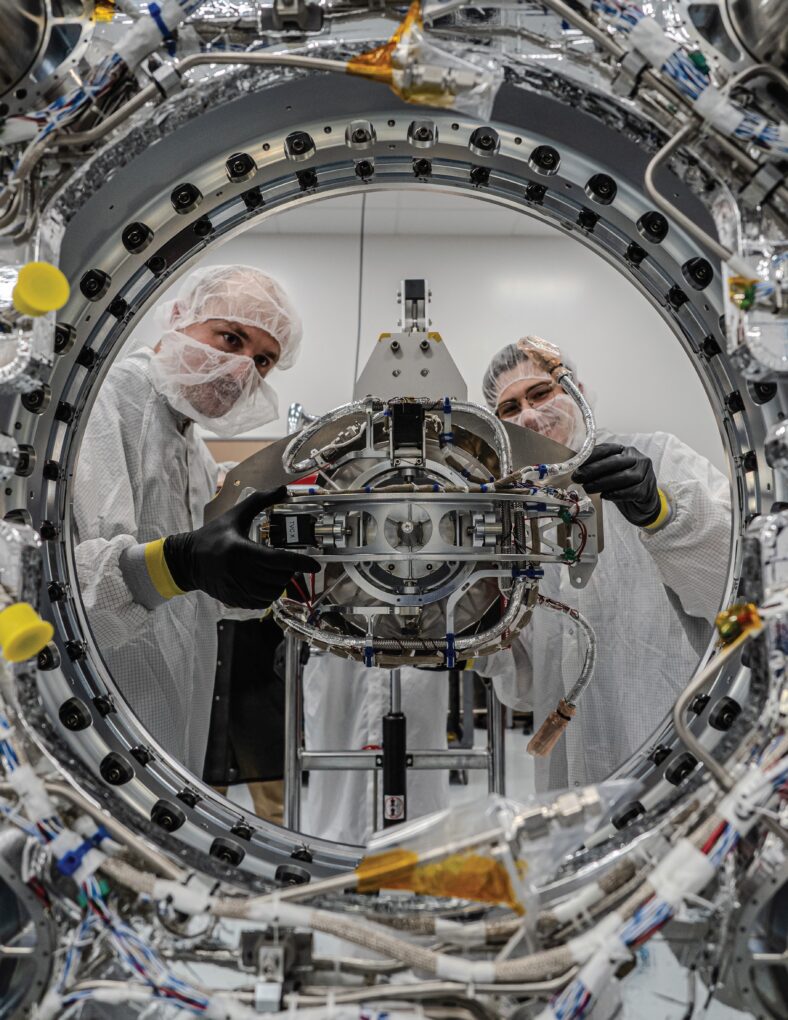

So the two spacecraft that are going to Mars is very much not pie in the sky. In fact, they’re sitting at the Cape Canaveral right now awaiting their launch vehicle. They’re not launching on a Rocket Lab vehicle, they’re launching on a different vehicle. So as long as the launch vehicle launches, then they will be in Mars very shortly. And I think that kind of talks to the power of Rocket Lab. The amount of people that have proven that they can build an interplanetary probe, you’re talking about very rarefied air, maybe Boeing, Lockheed, that’s pretty much it. So we’ve really come in and disrupted that. And part of the reason is if you can build two satellites to go to Mars, it pretty much shows to the world that you can build any satellite that you put your mind to. So that’s why it was important for us to do those.

There are two other major components that are integral to the conversation: one is speed-of-build and the other is cost. And you built them in three-and-a-half years, right?

It’s not untypical if you’re going to go to Mars, your program contract starts with a ‘B’ in the front and generally a decade. And we built not one but two spacecraft in three-and-a-half years that are going for some tens of millions of dollars. So it is just a complete upending of planetary science and the way that people think about it.

What about the ‘Life on Venus’ project?

Venus is a personal project. It’s a ‘nights and weekends’ kind of deal for Rocket Lab. It’s a purely philanthropic funded mission. And really the reason why I’m so interested in going to Venus is that there was some phosphine gas discovered in the clouds of Venus by Sarah Seager and her science team a few years back. And currently, the only known mechanism for creating phosphine is through organic symbiology or life. So this is kind of an unashamed attempt for a private company to go to the clouds of Venus, put a probe in there. The probe survives about 120 seconds and has a real digital go-no-go gauge for is there life in the clouds of Venus? And I think the reason why I’m personally very attached to that is that I think as a human species, we have not answered the question: Are we the only life in the universe or not currently?

Currently, if you want to take the scientific method, there is no evidence of life outside Earth at all that we have proven. And I think that’s a pretty fundamental question to answer. If you could find life in the clouds of Venus, then you can pretty much conclude that if it can survive in the clouds of Venus, then it’s most likely prolific throughout the universe. So I think answering that question is one of humanity’s greatest kind of questions. It’s like since the beginning of time, folks looking up at the sky going, “Are we the only people here or not?” And we have a chance of answering that question. I think the chance is extremely remote that the question can be answered or we’re successful, but still we have a chance. And while there’s a chance, I’m extremely devoted to giving it a crack.

Is there a rough goal of you can get this done by?

I made this mistake before because I was hoping to do it this year, but then we were commercially extremely successful, so we have no nights and weekends to work on the project. So we just keep pushing it out year by year. But I would say that we made great progress: the scientific instrument is built, the science team is together, the probe is under construction and all of those things. So we’re just tinkering away on it when we can and we’ll bring it together when it comes together. The good thing is that Venus isn’t going anywhere.

Is developing a rocket that’ll get you to Venus the obstacle?

No, so we already developed the rocket in spacecraft. We did a mission called Capstone for NASA two years ago where we used the weak boundary effects of Earth to slingshot a probe all the way out to the moon. We’ve already demonstrated that a spacecraft and our rocket can do it. Like I say, it’s just a matter of resources to put on it and finding a spare rocket in the back of the factory.

What are the positives and/or negatives you gleaned from the Wild Wild Space doc?

To be honest with you, it was just not a priority to me. Never was. I think if you talk to [PR Manager] Muriel, she’ll say that I tried everything I could do to kill it because I’m not seeking fame and fortune, I’m just trying to build a rocket, right? So I would say I was a reluctant participant. I just want to get on and do my shit. And I think a credit to [writer] Ashlee [Vance] and [director] Ross [Kauffman], what you saw is real, right? What you got is what you got. There was no kind of kind of over dramatic of anything really. On the list of one to 10 of important things, however, that’s like .01.

You receive about 40% of the screen time, so it really feels like a race between you guys.

There was no race. There was never a race.

it seemed like [Astra founder] Chris Kemp came to you pretending to be a documentarian interested in learning how you work, and then he was really stealing some of your IP, or at least ideas. I’m sure there’s some people you want to see succeed, and some who you don’t mind seeing fail. Was there any satisfaction in seeing Astra expose themselves as fraudulent?

Here’s the deal. There’s no surprise that straight after they visited us, they had a launch vehicle that was competing with us. And a bunch of technologies like electric turbo pumping; their vehicle was electrically turbo pumped. There was no kind of surprises there. I think the movie was quite charitable in the way they portrayed Chris. I think that there’s certainly a little bit darker aspects in there that if you wished, I’m sure you could see, but we never fought any of those intellectual property battles because it would just be a waste of money. To me, it was so very obvious that that was going to be a failure. I don’t know. It’s like being a baker and leaving the flour out the bread. There’s no point. Even if they’ve stolen your oven, there’s no point spending money because there’s no flour in the bread, it’s not going to work.

And the same was with Virgin; it was so obvious that that business model was going to fail. You can’t spend $1.2 billion and then sell a rocket and compete with us at a cost basis that is just an order of magnitude different. It was obvious that that was just a matter of time until it fails. And then there’s companies right now that you can point to that are exactly the same. Unfortunately, the kind of extinguishment of charlatans and Theranos’s in this industry is not complete. There’s still a couple to go. I’m not sure that I felt huge satisfaction because I also know that all of the engineers there work their ass off. And I know how hard it is to even put anything on the pad. It is very hard.

And it doesn’t do the industry any good. Part of our challenge as a publicly traded company is we have the best house in the shittiest neighborhood because with Astra failing, all that does is it tells investors that if you want to lose money, put it in space. Same with Virgin Orbit and a whole bunch of other space companies that have just literally shat the bed. So there’s no great win here. I mean, Chris just burned a whole bunch of investors’ money, mainly their Mas and Pas at home. Damaged the space industry. A whole bunch of engineers worked their ass off for no reason. And so I guess I would like to think that I’m bigger than that to sit there chuckling away, because I just don’t think any good came out of it at all. I’m just disappointed that that happened.

I’ve been to your neck of the woods, southern New Zealand. It’s an amazing, beautiful country — but also very small. It’s remarkable you’ve grown Rocket Lab from those humble roots to compete against the Chinas, SpaceXs and NASAs of the world. You were even knighted recently in the New Zealand Order of Merit. Is there now more joy or pressure from being considered one of New Zealand’s shining stars?

Well firstly yes, the origins of this company are in New Zealand and we have about 600 people of our 2,100 people in New Zealand. We are a US company; we have been since 2013 when I raised that first bit of capital. But yeah, I mean there is something special about New Zealand and New Zealand engineers… I feel like I’m tremendously lucky really to have been able to build the company here and then give back.

But look, it always takes a village and anybody who tells you otherwise is a liar. I mean, so many people have put their faith and trust in me personally. And even today as shareholders, I take that very, very seriously. And so there’s a tremendous amount of people who have nurtured and supported us. [Acknowledgement is] not really a driver, but I think the country has recognized those efforts in the highest merit possible — which makes for a proud mom, that’s for sure.