As a health writer, I’ve watched wellness trends come and go, each one claiming to be as life-changing as the last.

“I read that [insert detox drink or mushroom coffee here] is really good for you,” people have said to me with promising smiles, time and time again. But they didn’t actually read the information anywhere. Most likely, they watched a conventionally attractive woman in a matching athleisure set sing the elixir’s praises on Instagram while plugging a brand-affiliated discount code. Or, they watched someone hop on camera to share their personal reasons for disavowing once universally accepted, scientifically-backed health advice like wearing sunscreen or getting vaccinated from infectious diseases like COVID-19 and took the opinion as fact.

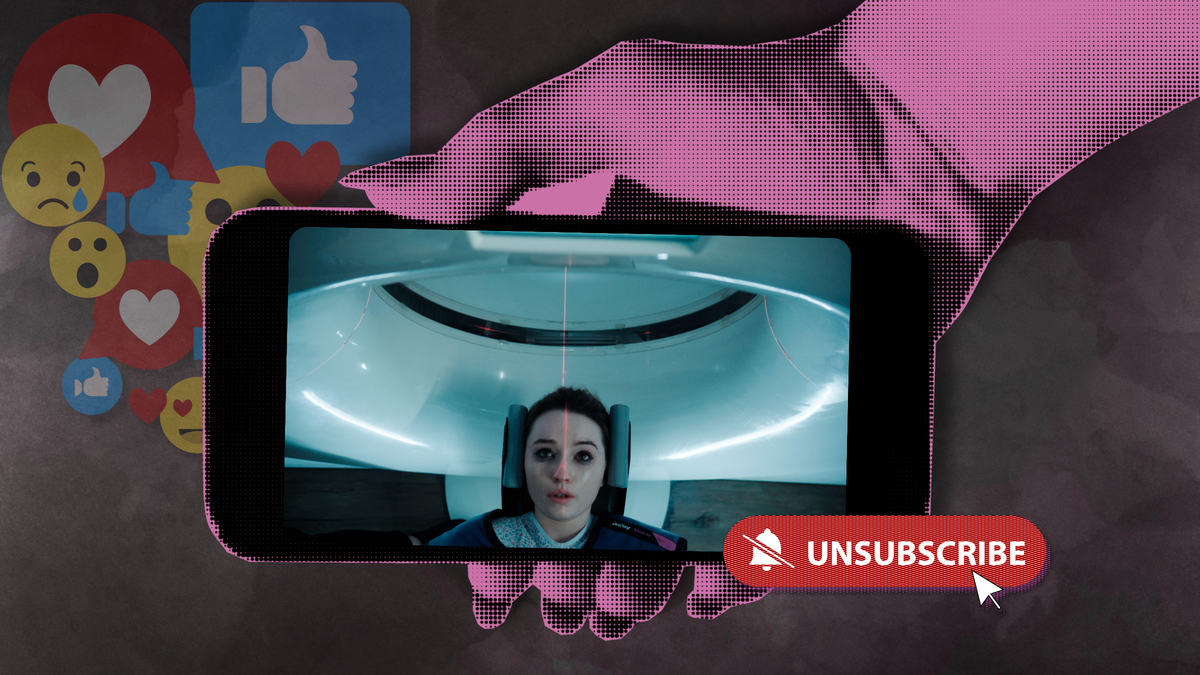

Netflix’s new original series Apple Cider Vinegar, marketed as a “true-ish story, based on a lie,” explores just how detrimental those embellishments can be. The show is a fictional retelling of wellness influencer Belle Gibson’s real fall from grace. As an ambitious entrepreneur, she establishes an online following, mobile app, and cookbook rooted in the lie that she healed her terminal brain cancer with food, all while omitting the fact that she was never actually ill. Meanwhile, in a secondary plot, a peer-turned-rival influencer scrambles to hide her very real, active sarcomas from an equally robust following while selling the organic juices and coffee enemas that she claims put her in remission.

The moral of the story: neither schtick is sustainable, and both lead to more harm than good.

The Allure of Social Media Wellness Trends

“The wellness space is flooded with misinformation, fear-based narratives, personal anecdotes, and quick fixes,” says registered dietitian Alex Larson. “This type of information spreads faster than nuanced, science-backed advice.”

Such misinformation, defined by the United States Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) as “false, inaccurate, or misleading according to the best available evidence at the time,” is a growing problem. There are a few reasons why.

“In an age of instant gratification, it can be incredibly tempting to try to find quick solutions to all of our problems with a swipe of an app,” says Dr. Austin Perlmutter, a board-certified internal medicine physician and researcher specializing in brain health. That’s especially because there is a “fundamental issue with access to healthcare in the United States,” adds Dr. Rekha Kumar, a triple-board-certified endocrinologist and professor at Weill Cornell Medical College, and finding a doctor can be overwhelming, expensive, and frustrating. There is also a general, wide-reaching distrust of the medical industry, Perlmutter adds, for many reasons—the main one being that poor experiences with the health care system are so common. “Many people with legitimate concerns are turned away for ‘not being sick enough’ or ‘not motivated enough,’ which can scare them from seeking future care,” Kumar explains.

Posting a dramatic before-and-after transformation, be it genuine or not, is one of the easiest ways to go viral online.

All of this makes it tempting for people to take health matters into their own hands—especially when information is so easily accessible. “There’s a sense of community that comes along with chatting online and being a part of the wellness movement,” adds Gail Cresci, a registered dietitian, researcher, and member of Bragg’s scientific advisory board, which can be very alluring, she says.

As for influencers’ part in it all, they’re paid to “package advice in a way that feels relatable compared to the approach that doctors may provide,” explains Larson, which lands nicely with people in vulnerable states in search of validation or answers. If users engage with that type of content—meaning they like it or comment on it—they’re very likely to be algorithmically delivered more of the same, reinforcing the echo chamber of falsehoods, add Kumar and Perlmutter.

How to Spot Bad Wellness Advice Online

The USDHHS says that one of the most impactful ways we can throttle the spread of misinformation is by learning how to identify it and question it when we do. Here’s how to do just that.

1. Check the Source’s Credentials

If you’re learning from a person who is talking to their phone’s front camera, click on their profile and read more about their background.

If they’re giving medical advice, do they have the certifications to do so? Look for specific letter credentials like MD, medical doctor, RD or RDN, a registered dietitian or registered-dietician nutritionist, respectively, or CPT, certified physical trainer, that go beyond vague placeholder titles. “Anyone can call themselves a nutritionist,” says Cresci. Similar words that should raise red flags are “health coach” or an undefined, non-credentialed “expert.”

Also, check the profile’s username and activity history to ensure you aren’t interacting with a fake or spam account. “Last year, I came across a TikTok that impersonated me by posting my videos and asking people to Venmo or Zelle them for access to GLP-1 medications,” recalls Kumar. “People easily fell prey to this scam because the account was using my real content.”

2. Cross-Check Information Before Believing It, and Especially Before Sharing It

Getting information from a single source simply isn’t enough. Before you store something in your memory or discuss it with others, do a quick search of your own to corroborate the facts.

Look to reputable sources “like medical journals or government health websites,” says Jennifer Pallian, a registered dietitian, such as the National Library of Medicine or the American Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. And even then, don’t be swayed by a single study’s conclusions. “One study doesn’t prove a trend,” says Larson. Established research backed by multiple studies and credentialed professional input is the most reliable.

3. Be Wary of Quick Fixes or “Miracle” Cures

Posting a dramatic before-and-after transformation, be it genuine or not, is one of the easiest ways to go viral online.

Anything that promises instant results—fad diets, workout programs, supplements—is something to be wary of right away. “As an endocrinologist, I know about all the fad diets and quick fixes that promise to help you lose ten pounds in a week. To set the record straight once and for all: those trends never work,” says Kumar. They’re “unsustainable or misleading at best, and could put your health at risk at worst,” she adds. Anything that truly sticks, health-wise, takes time and consistency.

Put differently: “If it sounds too good to be true, it probably is,” says Larson. “Just because it worked for one influencer doesn’t mean it’s science-backed and safe for you to do.”

4. Ask Yourself: “Am I Being Sold Something?”

If there’s a shopping link to click or a promo code to punch in, think twice before proceeding or taking intel to heart. “Likely, the influencer is pushing a product or service that suits their agenda, not your well-being,” says Cresci.

This is especially the case for self-help books or supplements, adds Kumar. “It’s trendy for influencers to have supplement brands, and while most won’t harm you, you are likely falling prey to marketing tactics,” she explains.

The bottom line is: question everything, and remember that no piece of guidance is one-size-fits-all. “Even if you’ve confirmed the source as legitimate, you should always speak to your doctor before taking medical advice,” says Kumar. “What works for the majority of people might not work for you.”

Want more of Outside’s Health stories? Sign up for the Bodywork newsletter.

The post Netflix’s Apple Cider Vinegar Shows Just How Scary Health Misinformation Can Get appeared first on Outside Online.