As headlines go, “Social Media is Bad” doesn’t raise many eyebrows these days. TikTok and its ilk are said to be harming mental health, stifling creativity, eroding privacy, fueling disinformation, undermining national security, and so on. These are all big issues worthy of careful debate. But there’s a narrower and more tangible risk that Sweat Science readers might be concerned about. What if social media is making us slower?

A recent study in the European Journal of Sport Science, from Carlos Freitas-Junior of the Federal University of Paraiba in Brazil and his colleagues, presents data on what happens when athletes scroll on their phones before training sessions. Surprisingly, it doesn’t just mess with that specific workout. Instead, over time, the athletes make smaller gains in performance. The findings tell us something about social media—and they also suggest that the benefits of a workout may depend in part on the state of mind you’re in while doing it.

The Problem(s) With Social Media

Several studies over the years have examined social media use in athletes. Most famously, back in 2019 researchers at Stony Brook University found an association between late-night tweeting (as it was then called) and next-day game performance in NBA players. If the players were tweeting after 11:00 P.M., the players tended to score fewer points, grab fewer rebounds, and shoot less accurately the next day.

You might argue—correctly—that the problem here is sleep deprivation rather than social media. But other studies have found direct links between the usage of apps such as TikTok and sleep patterns in young athletes, suggesting that the root of the problem is the apps. Researchers have also linked social media use to mental well-being and even eating disorders in athletes, both of which impact performance.

These indirect impacts aren’t always straightforward: the TikTok-hurts-sleep study also found that Instagram usage was associated with greater calmness, for example. But there’s also a more immediate concern, which is that social media apps leave you mentally fatigued, which in turn directly compromises your endurance and decision-making abilities.

The Mental Fatigue Debate

The study that kicked off the modern conversation about mental fatigue in sport was a 2009 experiment from a researcher named Samuele Marcora. He showed that 90 minutes of doing a cognitively challenging computer task reduced cycling endurance by about 15 percent compared to spending 90 minutes watching a documentary.

More studies followed, each investigating different types of mental fatigue and their effects on different types of athletic performance. Many of them echoed Marcora’s original results, but not all of them. One of the big unresolved questions is the extent to which the findings apply in real life. If you have to write an exam or do your taxes right before you run a marathon, that’s probably bad news. But what about the normal activities we engage in on a daily basis—like scrolling through the social media apps on your phones? Do they induce sufficient mental fatigue to affect performance?

Back in 2021, a swimming study found that 30 minutes of social media use hurt athletes’ times in 100- and 200-meter freestyle trials, but not in the 50 meters. Another study found that boxers made worse decisions after using social media, but that their jumping performance was unaffected. Yet another found no effect of social media use on strength training performance. These results are consistent with the general pattern of research on mental fatigue and related stressors like sleep deprivation: with sufficient motivation, you can still exert maximal force, but your decision-making and endurance may be compromised.

What the New Data Shows

Freitas-Junior’s new study looks at volleyball players, testing their jumping performance and their “attack efficiency,” a measure of how hard and how accurately they can hit the ball in a sequence of attacks. What’s different about the study is that it looked at long-term rather than immediate effects. Fourteen athletes spent half an hour before practice either using Facebook, WhatsApp, and Instagram on their phones, or watching documentaries about the history of the Olympics. After three weeks, their performance was assessed and then they switched groups and repeated the process for another three weeks.

At the end of the three-week period, jumping performance wasn’t affected under either condition, but athletes’ attack efficiency was worse following the three weeks of social media use. The difference was statistically significant, but to be honest the data isn’t very convincing.

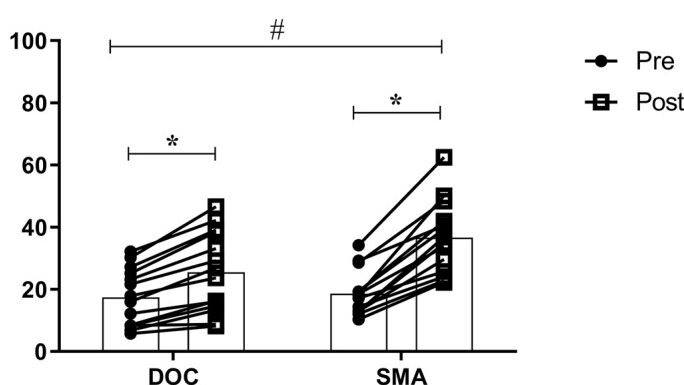

For starters, take a look at the mental fatigue data. This shows how much, on average, mental fatigue (on the vertical axis) increased after watching the documentary (DOC) or using social media (SMA):

Athletes’ mental fatigue before and after watching a documentary, and before and after social media use (Illustration: European Journal of Sports Medicine)

This is nice clean data. Watching the documentary increased the subjective perception of mental fatigue in almost every individual. Using social media increased it even more, again with uniform results in all the individuals. We can say with confidence that social media use increases mental fatigue compared to chilling with a doc.

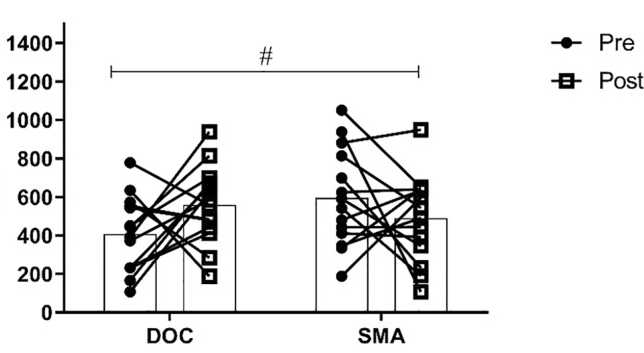

Now take a look at the attack efficiency data, measured in arbitrary units where a higher number is better:

This time the individual data is all over the map. The statistical analysis tells us that, on average, the social media group got worse while the documentary group got better. This average effect may or may not be real—only more and larger studies can confirm if it is. Based on the body of previous research, I’d guess that it’s probably real. But the pattern is so inconsistent on an individual level that I’d hesitate to use it as a basis for advice to athletes. Some athletes got better after social media use. That might be a fluke, or it might indicate that they have a healthier relationship with their apps such that a little phone time before practice gets them in a better headspace.

In the end, then, the narrative isn’t as tidy as we might like. It’s not that social media is uniformly bad, will leave you mentally fatigued, and will automatically rob you of training gains. There’s still a valuable message here, though. The things we do—social media, yes, but also real-world socializing, reading a book, listening to music, working, commuting, daydreaming, and so on—affect our mental state and readiness to perform. We all respond to these things differently, so there’s no universal list of dos and don’ts. But it’s worth figuring out what gets you in the right headspace and leaves you mentally energized, so that you can replicate it when it matters.

The post Why Social Media Might Be Making You Slower appeared first on Outside Online.