Sham surgery trials prove that procedures like non-emergency stents offer no benefit for angina pain—only risk to millions of patients.

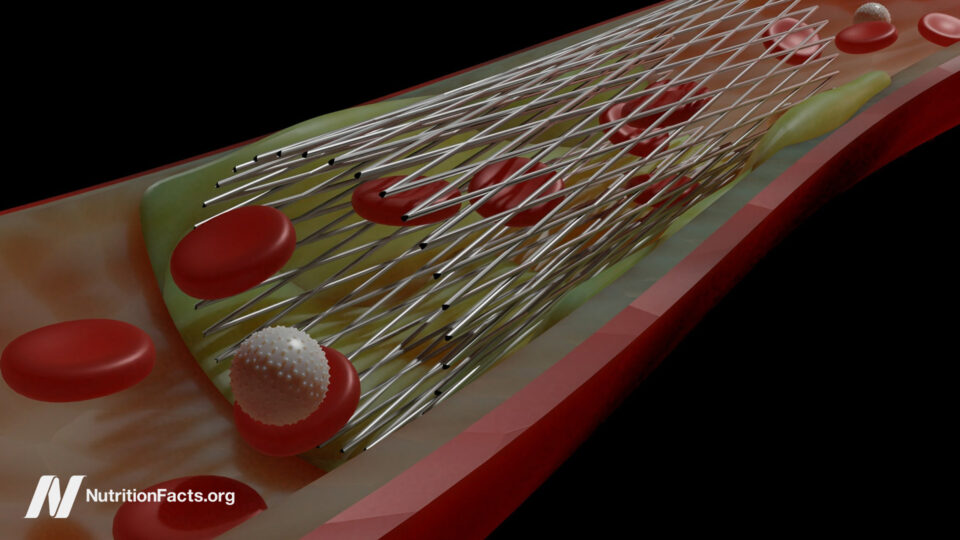

Angioplasty and stents—percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)—for stable, non-emergency coronary artery disease are among “the most common invasive procedures performed in the United States.” Though they appeared to offer immediate relief of angina chest pain in stable patients with coronary artery disease, that didn’t actually translate into a lower risk of heart attack or death. This is because the atherosclerotic plaques that narrow blood flow tend not to be the ones that burst and kill us. Symptom control is important, though, and is much of what we do in medicine, but cardiology has a bad track record when it comes to performing procedures that don’t actually end up helping at all.

Case in point: internal mammary artery ligation. Though it didn’t make much anatomical sense—why would tying off arteries to the chest wall and breast somehow improve coronary artery circulation?—it worked like a charm with immediate improvement in 95 percent of hundreds of patients. Could it have just been an elaborate placebo effect, and surgeons were cutting into people for nothing? There’s only one way to find out: Cut into people for nothing.

As I discuss in my video Do Heart Stent Procedures Work for Angina Chest Pain?, people were randomized to get the actual surgery or a sham (or fake) surgery where patients were cut open and the surgeon got to the last step but didn’t actually tie off those arteries. The result? “Patients who underwent a sham operation experienced the same relief.” Check out the testimonials: “Practically immediately, I felt better.” “I’m about 95 percent better.” “No chest trouble even with exercise.” “Believe I’m cured.” And these are all people who got the fake surgery. So, it was just an extravagant placebo effect. Think about it. “The frightened, poorly informed man with angina [chest pain], winding himself tighter and tighter, sensitizing himself to every twinge of chest discomfort, who then comes into the environment of a great medical center and a powerful positive personality and sees and hears the results to be anticipated from the suggested therapy is not the same total patient who leaves the institution with the trademark scar.” He hears how great he’s going to feel, goes through the whole operation, and leaves a new man with that trademark scar.

One sham patient was actually cured, though. “The patient is optimistic and says he feels much better.” The next day’s office note reads: “Patient dropped dead following moderate exertion.” This has happened over and over.

What if we burn holes into the heart muscle with lasers to create channels for blood flow? It seemed to work great until it was proven that it doesn’t work at all. Cutting the nerves to our kidneys was heralded as a cure for hard-to-treat high blood pressure until sham surgery proved that procedure was a sham, too. “The necessity for placebo-controlled trials has been rediscovered several times in cardiology, typically to considerable surprise.” Before they are debunked, “often a therapy is thought to be so beneficial that a placebo-controlled trial is deemed unnecessary and perhaps unethical.” That was the case with stents.

Hundreds of thousands of angioplasties and stents are done every year, yet placebo-controlled trials have never been done. Why? Because cardiologists were so unquestioningly sure it worked “that it might be unethical to expose patients to an invasive placebo procedure.” Why perform a fake surgery to prove something we already know is true? “When patients are aware they have had PCI, they have a clear reduction in angina and improved quality of life.” But what if they weren’t aware they had a stent placed inside them? Would it still work?

Enter the ORBITA trial. After all, “anti-anginal medication is only taken seriously if there is blinded evidence of symptom relief” against a placebo pill, so why not pit stents against a placebo procedure? “In both groups, doctors threaded a catheter through the groin or wrist of the patient and, with X-ray guidance, up to the blocked artery. Once the catheter reached the blockage, the doctor inserted a stent or, if the patient was getting the sham procedure, simply pulled the catheter out.”

The researchers had problems getting the study funded. They were told: “We know the answer to this question—of course, PCI works.” And that’s even what the researchers themselves thought. They were interventional cardiologists themselves. They just wanted to prove it. Boy, were they surprised. Even in patients with severe coronary artery narrowing, angioplasty and stents did not increase exercise time more than the fake procedure.

“Unbelievable,” read the New York Times headline, remarking that the results “stunned leading cardiologists by countering decades of clinical experience.” In response to the blowback, the researchers wrote that they “sympathize with our community’s shock and its instinct to invalidate the trial. Applying a positive spin could have smoothed the reception of the trial, but as authors we have a duty to preserve scientific integrity.”

While some “commended them for challenging the existing dogma around a procedure that has become routine, ingrained, and profitable,” others questioned their ethics. After all, four patients in the placebo group had complications from the insertion of the guide wire and required emergency measures to seal the tear made in the artery. There were also three major bleeding events in the placebo group, so they suffered risks without even a chance of benefit. But “far from demonstrating the risks of sham-controlled PCI trials, this demonstrates exactly what patients are being subjected to on a routine basis, without evidence of benefit.”

Those few complications in the trial “are dwarfed in magnitude” by the thousands who have been maimed or even killed by the procedure over the years. Do you want unethical? How about the fact that an invasive procedure has been performed on millions of people before it was ever actually put to the test? Maybe “we should consider the absence, not the presence, of sham control trials to be the greater injustice.”

When a former commissioner of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration was asked at the American Heart Association meeting “whether sham controls should be required for device approval, he thought that it was more of a decision for the clinical community: ‘Do you want to get the truth or not?’”