Is heme just an innocent bystander in the link between meat intake and breast cancer, diabetes, heart disease, stroke, and high blood pressure?

In an editorial in the Journal of the American Medical Association, the chair of nutrition at Harvard pointed out that many plant-based meats, such as burgers made by Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods, can be high in sodium. An issue specific to the Impossible burger is the “heme (an iron-containing molecule) from soy plants added to the burger patty to enhance the product’s meaty flavor and appearance.” Safety analyses have failed to find any toxicity risk specific to the soy heme churned out by yeast, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has agreed that it is safe, both for use as a flavor and color enhancer. In other words, it’s just as safe as the heme found in blood and muscle in meat—but how much is that really saying?

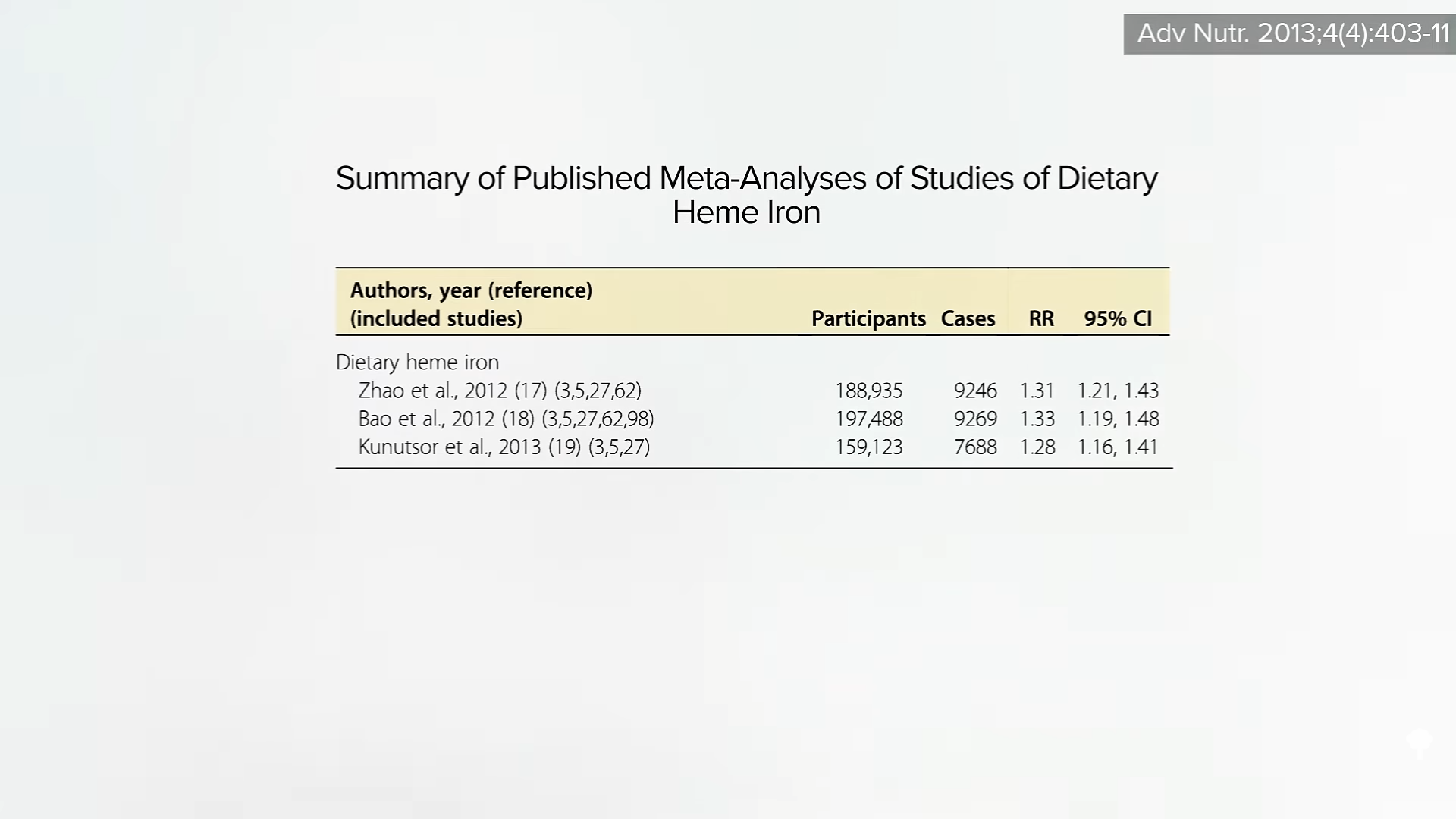

The concern raised in the JAMA editorial, for example, was that “higher intake of heme iron has been associated with…elevated risk of developing type 2 diabetes,” killer number seven in the United States. That isn’t all, though. “Higher dietary intake of heme iron is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease,” as well, as killers numbered 1, 4, and 13—heart disease, stroke, and high blood pressure. But since heme is found mostly in meat, heme intake may just be a marker for meat intake. It’s like with diabetes: Four meta-analyses have been published to date, and they all reported the same link, as seen below and at 1:25 in my video What About the Heme in Impossible Burgers?. But there are a lot of reasons meat may increase diabetes risk, like its advanced glycation end-products (AGEs), which are produced when animal products are baked, broiled, grilled, fried, or barbecued. So, how do we know that heme isn’t just an innocent bystander?

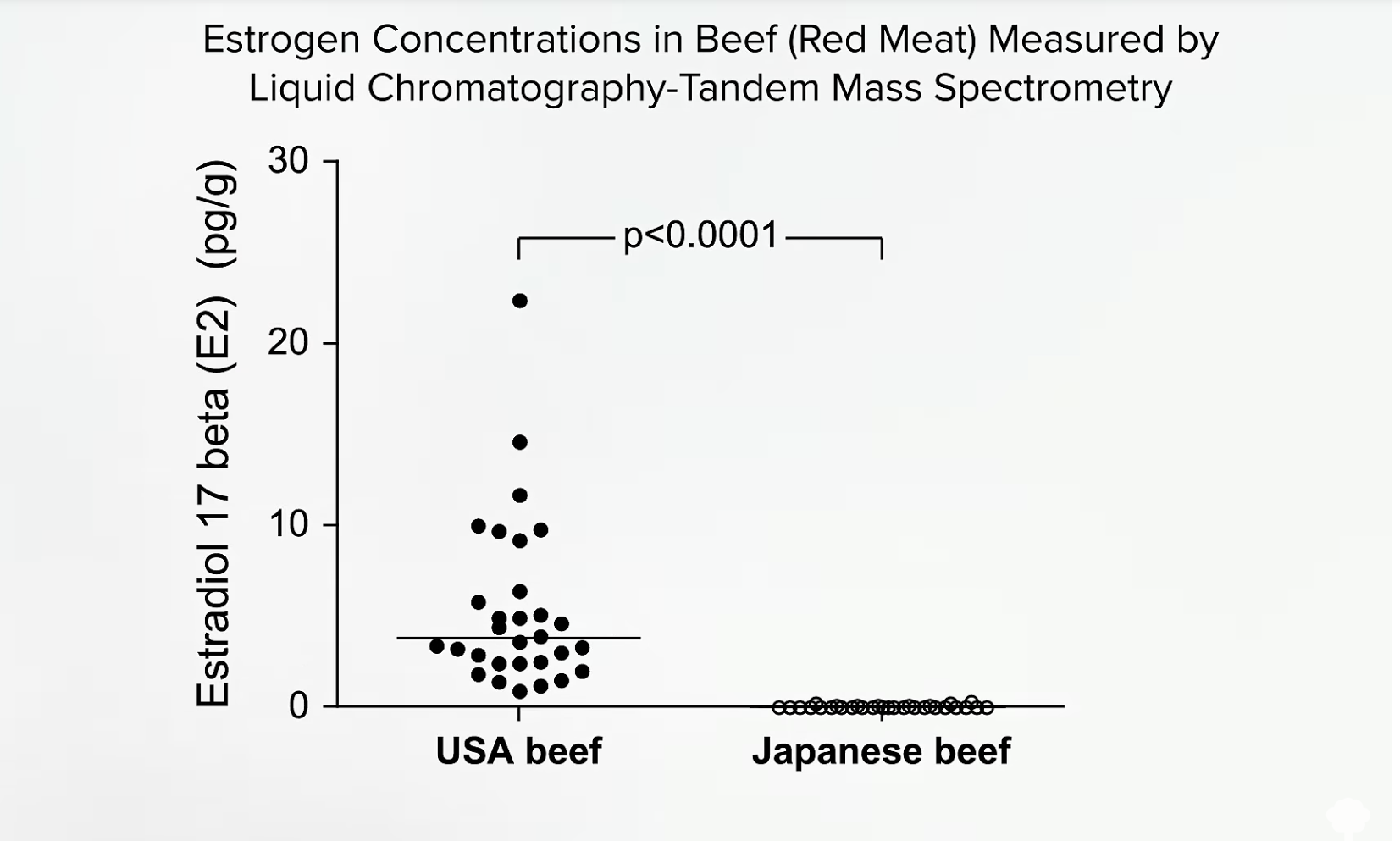

The same issue arises with the link between heme intake and increased breast cancer risk. Since heme iron comes from animal foods, it could be any of the other components in meat, like animal fat or meat mutagens, which are compounds in meat that can cause DNA mutations. And what about all the hormonal steroids implanted into cattle that may play a role in the development of breast cancer? A study in Japan found that beef imported from the United States contained up to 600 times the levels of estrogens like estradiol. You can see the comparison of U.S. beef to Japanese beef below and at 2:20 in my video. “Higher consumption of estrogen-rich beef due to hormone application might facilitate estrogen accumulation in the [human] body and thus affect women’s risk for breast cancer.” So, yes, heme iron intake was associated with breast cancer risk, but maybe that’s just because the heme and the hormones traveled together in the same package—meat.

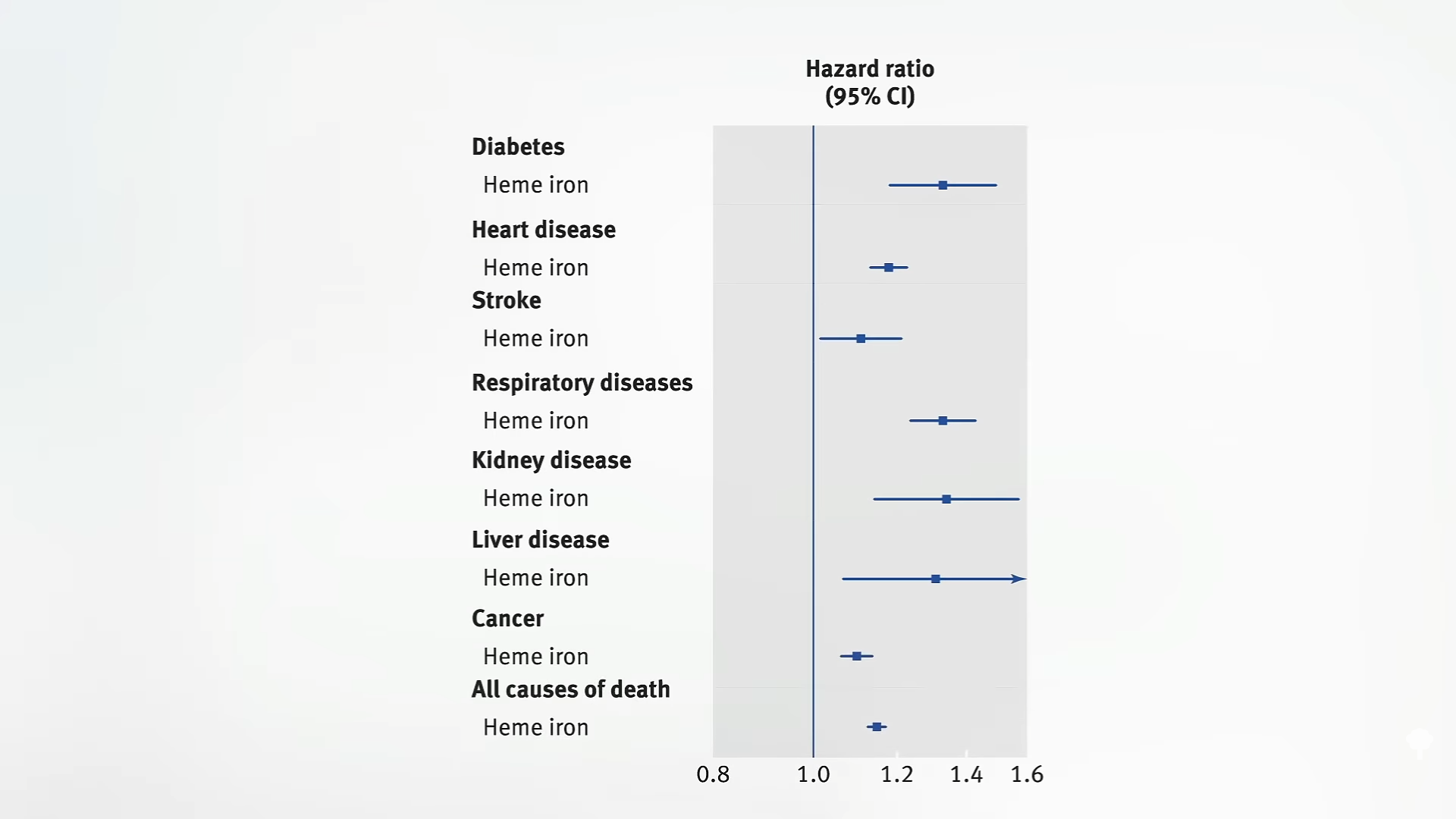

The NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study is about as good as any observational study can get. It is the largest prospective study on diet and health ever, following more than half a million men and women for more than a decade now. With such a huge dataset, its researchers could take advantage of the fact that different meats have different amounts of heme, so they could try to tease out the heme components, in effect, by comparing people eating different amounts of heme, but the same amount of meat, to see if heme is independently associated with the disease. And, indeed, that’s what they showed: “independent associations between the intake of heme iron and nitrate/nitrite in processed meat and mortality from almost all causes”—death from diabetes, heart disease, stroke, respiratory disease, kidney disease, liver disease, cancer, and all causes put together, as seen here and a 3:33 in my video.

The researchers calculated that about one fifth of the association between eating burgers and the shortening of our lifespan, for example, could be statistically accounted for by just the heme itself, but that’s assuming cause-and-effect. An “independent association” is still an association. You can’t prove cause and effect until you put it to the test in interventional studies.

Normally, we don’t necessarily care about the mechanism. When the World Health Organization designated bacon, ham, hot dogs, lunch meat, and sausages to be Group 1 carcinogens, meaning we know these products cause cancer in human beings, who cares if it’s the heme iron, the heterocyclic aromatic amines, the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, or the N-nitrosamines? They’re all wrapped up in the same place—processed meat—which we know causes cancer, so shouldn’t we try to stay away from it, regardless of the mechanism? With the advent of the Impossible Burger, we really do have to know, because, for the first time, we have a lot of heme without any actual meat, so we need to know if the heme itself is harmful. For that, we’ll have to turn to interventional studies, which we’ll cover next.

This is the sixth in a nine-part series on plant-based meats. If you missed any of the previous installments, see the related posts below.

Up next: