When I start planning a camping or backpacking trip, I think a lot about risk. What kind of equipment do I need to stay dry? To stay warm or cool? I think about having fun, but I also attempt to mitigate disaster. As a bit of an obsessive, I spend a lot of time contemplating what could go wrong in the hopes of having my time outdoors go without incident.

So, I took a deep dive into data around accidents in national parks and other public lands nationwide, to figure out where the real risks lie. This data can be hard to track, as many injured people treat themselves, or receive first aid from a friend or family member, or transport themselves for treatment at a hospital. Unlike fatality reports, much data is lost in the process.

What Does the Data Say?

A study conducted in 2003 surveyed hikers on the Appalachian Trail, who’d been hiking for at least seven days. They were asked to complete a questionnaire around factors like injuries, and illnesses, along with practical measures they’d taken to avoid those things. That sounds like the kind of data that should be relevant to any of us going backpacking this summer.

The results? The most common cause of injury was blisters to the feet, followed by sore joints. The most frequent medical complaint was diarrhea. Filtering water, practicing good hygiene, and cleaning cooking implements correlated with avoiding that complaint. 24 percent of respondents reported tick bites.

Here are the myths and facts of water filtration. And tick bites are just as easy to avoid as E. Coli. Wearing appropriate clothing and taking advantage of modern chemical treatments can seriously reduce the odds of picking one up.

Where’s the juicy stuff, I wondered? I wanted to read about grizzly bear maulings and hiking poles being surgically removed from groins. A study from 2007 looked at injuries requiring activation of Yellowstone National Park’s Emergency Medical System. Surely Yellowstone, with its large predators and geothermal activity will deliver something gruesome.

In a two-year period, Yellowstone’s EMS responded to 306 injuries that generated records reviewed by the study. In 59.2 percent of those cases, victims were able to be treated at the scene, and did not require transportation to a medical facility. 77.4 percent of incidents involved soft tissue lacerations—cuts—only 8.8 percent involved a broken bone.

But what if you do encounter a grizzly while visiting Yellowstone? It turns out the bear spray that’s become the accepted answer is more of a placebo used to prevent tourists from carrying guns than it is a realistically capable tool. Fortunately there’s some very easy advice that’s statistically proven to deliver better results.

A larger study applied similar methodology across the park system between 2007 and 2011. It found that EMS responded to 45.9 injuries per million park visits. This is a substantially lower rate than that of, say, annual emergency department visits per-million people in the general population, according to the Centers for Disease Control. But that’s an imperfect comparison. People exist in the world 365 days out of the year. The average visit duration across the national park system is 7.44 hours.

That study found that 43 percent of EMS activations park service-wide involved simple first aid. 29 percent were in response to medical emergencies like heart attacks. Only 28 percent of activations involved traumas.

It seems it’s hard to find juicy data around gruesome injuries in national parks simply because, relative to the outside world, there just aren’t that many.

A study published in 2009 by Wilderness and Environmental Medicine studies all Search and Rescue operations across all national parks that occurred between 1992 and 2007. It found there were an average of 4,090 each year. The purpose of that study was to compare cost to efficacy, not to tabulate causations. Of all 65,439 SAR operations studied, the rescued victims were neither ill nor injured in 51,541 cases. In those cases, victims were likely lost, unable to return to a trailhead, or feared exposure. Activities requiring rescue correspond to those most likely to result in death in the main park service data set—hiking and boating. The study found that 13,211 people would have died without SAR intervention; these operations are saving more people than the total number of deaths across parks every year.

What About Deaths in National Parks?

If you’re curious about deaths, the most complete set of data comes from the National Park Service. A a single, nationwide agency responsible for the safety of hundreds of millions of annual visitors, NPS collects more data around human behavior in the outdoors than any other entity I know. Its most complete set of data comes from human fatalities, since those are the subject of significant reporting and investigation.

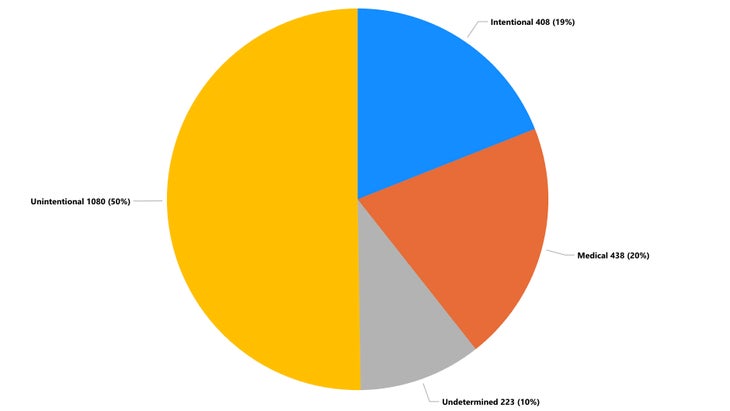

Looking at the NPS mortality dashboard for causations, we can see data like this:

Out of all deaths in national parks, intentional causes (suicides and homicides), medical causes, and undetermined (which are likely a mix of the first two categories) make up 50 percent of all fatalities. Unintentional causes—accidents—make up the other half.

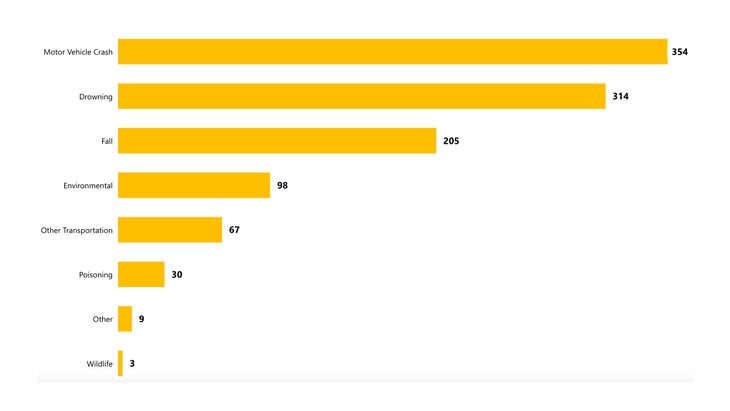

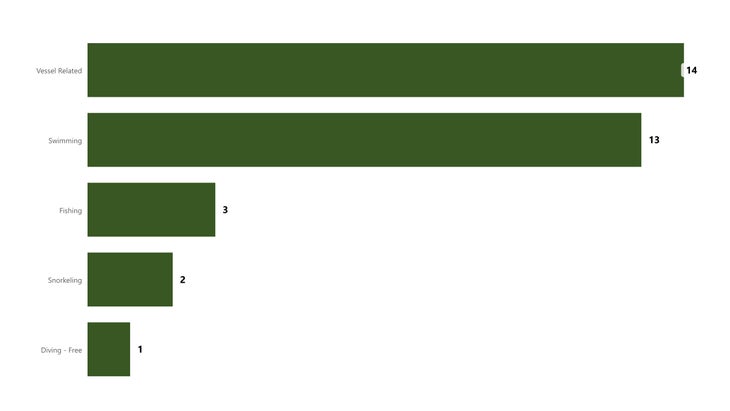

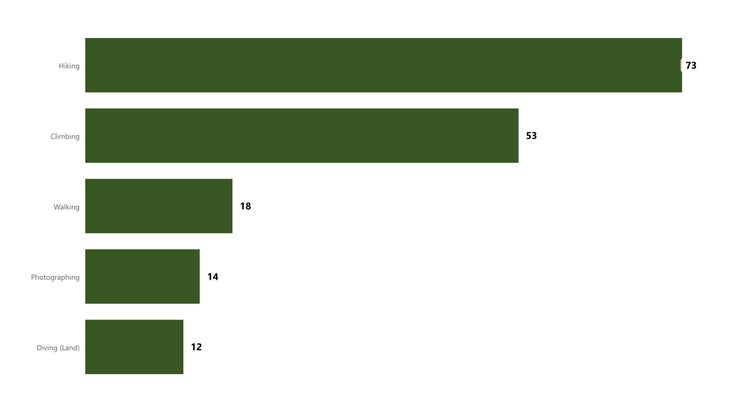

This data set runs from 2014 to 2019. Of those accidental deaths, the most common cause was motor vehicle crashes, followed by drowning, next come falls. These causes likely sound a lot less dramatic than you’d expect for places with mountains and bears. And they get even less dramatic when you dig into them. The largest group likely to drown in national parks are men aged 45-54, and the most common cause of those is boating accidents. The U.S. Coast Guard says alcohol is a factor in one-third of all boating accidents. Falls, too, involve fairly mundane circumstances. Many more of those occur while hiking rather than climbing, and most of the locations where people get into trouble are established hiking trails.

Deaths in national parks are also rare. Between 2014 and 2019, a total of 1,080 unintentional deaths occurred across the entire national park system. That’s out of 1.9 billion visits. You’re several times less likely to die while visiting a national park than you are to win the Powerball jackpot.

The odds of any particular type of accidental death skew heavily between individual parks, too. Most of those boating deaths occur in National Recreation Areas (which are managed by the park service and involve big bodies of water like Lake Mead). 39 people drowned there between 2014 and 2019. The park with the highest incidents of motor vehicle deaths was Great Smokey Mountains National Park, where people visit to drive the Blue Ridge Parkway. Distractions—looking at the views—are a major factor.

Visiting a national park, or recreating outdoors, remains very safe, despite the fact that these activities differ from our normal, daily behavior. Humans tend to experience a normalcy bias, where we perceive rare stuff to be much more dangerous than things much more statistically likely to kill us, so long as we do that more dangerous stuff more regularly. All that’s to say: If you want to avoid death and injury outdoors this summer, drive safely.

Wes Siler splits time between Yellowstone and Glacier National Parks. You can read his travel guidance and insights to both places on Substack.

The post How Common Is Getting Hurt in a National Park, Really? appeared first on Outside Online.